With Cornwall For Cornwall

Gans Kernow Rag Kernow

With Cornwall For Cornwall

Gans Kernow Rag Kernow

All the Latest News & Fixtures...

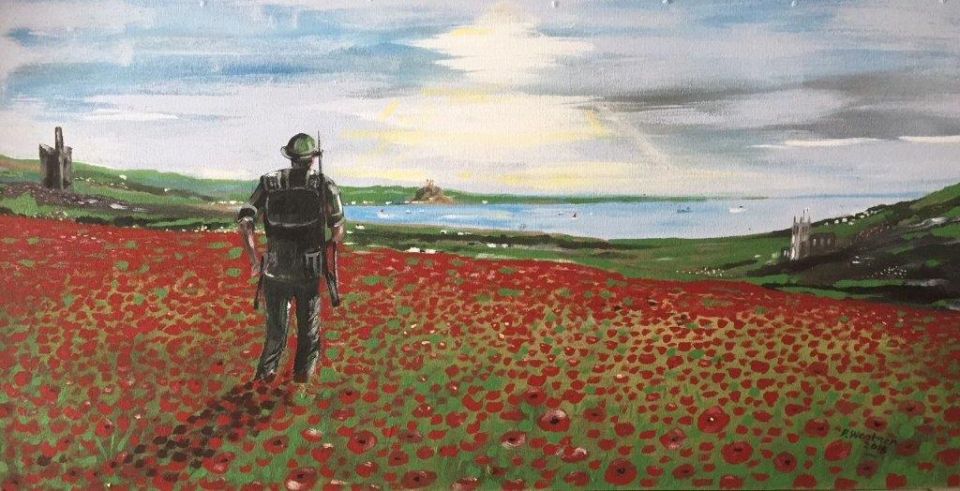

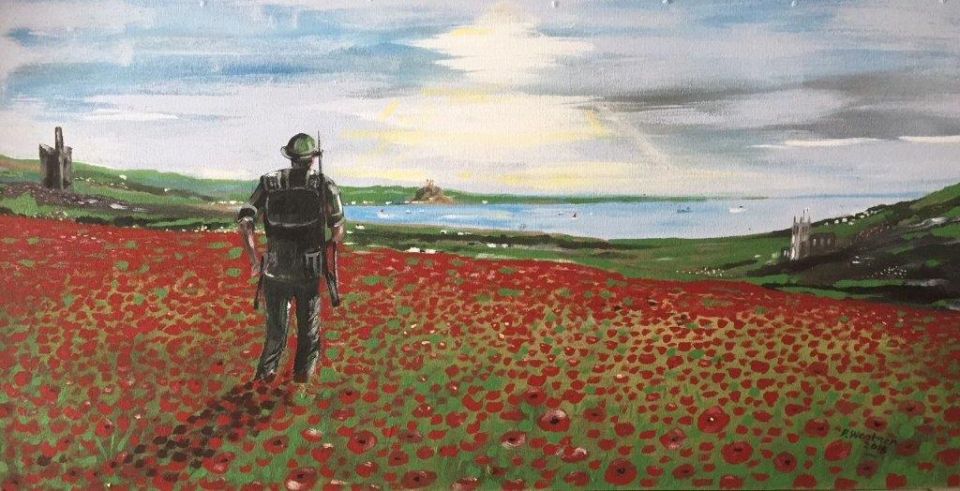

Commemorating 100 Years Since the End of WW1

by Phil Westren

During this very special commemorative year, Remembrance Sunday on the 11th November will mark 100 years to the day since the end of World War One.

The Cornish Pirates have a fixture that afternoon at home to Bedford Blues (ko 2.30pm), during which a match day collection will be held in support of the Royal British Legion. Also, in the morning, representatives of the club will lay a wreath upon the Penzance Memorial at Battery Rocks.

The Cornish Pirates fixture against Bedford Blues is a group match in the new Championship Cup competition. Cup matches are ‘All Pay’, with entry for those who purchase their tickets in advance being just £10, sit or stand anywhere on a first come first served basis.

Advance tickets can be purchased on-line at http://cornish-pirates.com/tickets/ or from the club’s ticket office, open Monday to Friday from 9am to 12 noon.

Entry on the day (space still permitting) will be £15 and £1 for children under 16.

The soldier overlooking Mount’s Bay image is a painting by Phil Westren

Because this year’s Remembrance Sunday marks 100 years since the end of WW1, there is also a special discount admission price for personnel serving in the Armed Forces, the Fire and Ambulance Services, the Police, plus Doctors, Nurses, the RNLI and the Coastguard Service. For any queries in advance, please email [email protected]

Admission to individuals wearing their uniform and/or displaying their ‘ID’ card, can on the day (space permitting) purchase a £5 terrace ticket at Gate 4, which is situated in the clubhouse corner of the ground. Entry will be space permitting.

For awareness, the gates at the Mennaye Field will be open at 12.30pm and just ahead of the 2.30pm kick-off there will be a minute’s silence. There will also be a collection on the day for the Royal British Legion.

* * * * *

Remembrance Sunday is held in the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth of Nations as a day “to commemorate the contribution of British and Commonwealth military and civilian servicemen and women in the two World Wars and later conflicts”. It is held on the second Sunday in November, the Sunday nearest to 11 November, Armistice Day, the anniversary of the end of hostilities in the World War One at 11am back in 1918.

This year, being extra special, the opportunity is taken to look back sports-wise to the period. Read on:

“How very different is your action to that of the men who can still go on with their cricket and football, as if the very existence of the country were not at stake! This is not the time to play games, wholesome as they are in times of piping peace. We are engaged in a life and death struggle.”

When Field Marshal Lord Roberts spoke these words on 29 August 1914, his message could not have been clearer: it was time for Britain’s sportsmen to stand up and be counted. Britain had declared war on Germany earlier that month and Lord Kitchener’s recruitment drive – “Your Country Needs YOU!” – was on its way to enrolling 500,000 men in its first four weeks.

Lord Roberts was speaking at the formation of a new 1,600-strong battalion of Royal Fusiliers by businessman from the City of London. This so-called “Stockbrokers’ Battalion” was the first of the “Pals’ Battalions” promoted by General Sir Henry Rawlinson as a way to encourage groups of friends and work-mates to serve together.

The campaign to enlist sportsmen intensified in early September with the public intervention of a leading writer and commentator, Arthur Conan Doyle.

The Sherlock Holmes author, an amateur footballer and MCC cricketer in his younger days, declared: “If the cricketer had a straight eye let him look along the barrel of a rifle. If a footballer had strength of limb let them serve and march in the field of battle.”

Posters used in the British recruitment campaign informed would-be soldiers that a German newspaper, Frankfurter Zeitung, was telling its readers: “Young Britons prefer to exercise their long limbs on the football ground, rather than expose them to any sort of risk in the service of their country.”

By the end of September, more than 50 towns and cities had established one or more Pals’ Battalions, among them sportsmen’s battalions, and three of those comprised mostly football players, club officials and supporters.

Heart of Midlothian and Leyton Orient signed up en masse, respectively to the 16th Royal Scots (known as McCrae’s Battalion) and the 17th Middlesex Regiment (the Footballers’ Battalion). The 15th West Yorkshire Regiment (known as “The Leeds Pals”) included Yorkshire cricketers, athletes and footballers.

It is impossible to quantify the precise number of British sportsmen who made the ultimate sacrifice in the war. Of almost nine million British Empire soldiers mobilised, around one in eight – or 1.1m individuals – were killed in battle or went missing, presumed dead. Another two million were wounded. On the front line, one in five perished.

Of 5,000 professional footballers at the time, more than 2,000 signed up. Using average mortality statistics, several hundred probably fell in the fields of Europe, with more dying later from their injuries.

Tottenham Hotspur staff enrolled and fought together from 1915, and the deaths of 11 of them were recorded in the club’s handbook after the war. Newcastle United lost seven men, the same number as Hearts, three of whose players – Harry Wattie, Duncan Currie and Ernie Ellis – died on 1 July 1916 alone, on the opening day of the Battle of the Somme. A team-mate, Paddy Crossan, was so badly injured that his right leg was tagged for amputation. He begged the surgeon: “I need my legs, I’m a footballer.” The leg was saved but Crossan, 22, died later of damage to his lungs from poison gas.

West Ham lost five players, and Orient three, all in the Somme, with others injured so badly their careers were over. At Bradford and Celtic, Preston and Hibernian, Bristol City, Arsenal, Manchester United and all points in between, star players were lost.

Cricket suffered a disproportionate number of deaths (almost one in six who went to war). At least 34 first-class players were killed among 210 county players who served. Kent and England’s Colin Blythe, a left-arm spinner regarded as one of the best of his era, took 100 wickets in 19 Tests. He was killed by random shell-fire on a railway line during the Battle of Passchendaele on 8 November 1917.

Rugby union prided itself as a sport that played its part. By the end of November 1914, every England international from the past year had signed up, while a 1915 war recruitment poster declared: “Rugby union footballers are doing their duty. Over 90 per cent have enlisted. British athletes! Will you follow this glorious example?”

There was an inevitable price to be paid. The England captain, Ronnie Poulton-Palmer (also Chairman of the Huntley & Palmer biscuit business in Reading), was killed by a sniper’s bullet at Ploegsteert Wood in 1915. A fellow officer reported that when he went around the company at dawn “almost every man was crying”. Ronnie was among 27 England internationals who died. Thirty Scottish international players lost their lives, and 11 Wales players.

Another England captain, Edgar Mobbs was denied a commission due to his age in September 1914, so he set about raising his own company and in 48 hours more than 400 men had volunteered – with Mobbs himself a private. He rose through the ranks to command the 7th Northampton Regiment (known as ‘The Mobbs Own’). Wounded three times during the War he was twice mentioned in dispatches and received the DSO in 1917. When he was killed leading a charge on the first day of the Battle of Passchendaele, leading a charge on a gun position, the whole county mourned. In 1921 a statue was erected in Northampton and the Mobbs Memorial Match was played for the first time and has been annually.

Torquay-born Arthur Leyland Harrison (1886 –1918) was an English Royal Navy officer, and World War I recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest and most prestigious award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to British and Commonwealth forces. Capped twice for England he is the only England rugby international to have been awarded the VC.

For most of the war he served aboard ‘HMS Lion’, seeing action at Heligoland Bight and Dogger Bank. He also saw action at the Battle of Jutland, and was mentioned in despatches.

Arthur was 32 years old and a Lieutenant-Commander when he died during the Zeebrugge Raid. His body was never recovered but for his actions, when he displayed ‘most conspicuous gallantry’, he was awarded the VC.

Among many other international rugby players to die in WW1 was Arthur James Wilson (1886 –1917), who was a member of Cornwall’s famous team that won the County Championship for the first time back in 1908. He was also in the side that won a silver medal that year when Cornwall, representing Britain, lost to Australia in the Olympics.

In 1909 Arthur was capped for England, playing in the forwards in the 11-5 win over Ireland at Lansdowne Road. Ronnie Poulton-Palmer (two) and Edgar Mobbs scored England’s three second half tries.

Born in Newcastle, he had played for Camborne School of Mines before taking his mining skills to the Gold Coast (now Ghana) and to South Africa. He also diverted to India as a tea planter.

Service records confirm that by November 1915 Arthur was serving in France with the Royal Fusiliers and that he died on the 31st July 1917, which was the first day of the Battle of Pilckem Ridge, being the opening attack of the main part of the Third Battle of Ypres known as Passchendaele.

Arthur has no known resting place but is remembered on Panel 6 and 8 of the Menin Gate at Ypres, and also in the chapel at Glenalmond College, at the Camborne School of Mines (Penryn Campus) and in Camborne church.

It is understood that during the War all local football ceased, but several rugby matches were played locally by Air Force men stationed in Newlyn – at the Seaplane Base near Penlee Quarry.

An interesting but sad event that took place just after the War broke out concerned the Newlyn club which owed the ‘Exiles’ RFC at Porthcurno a fixture which the Exiles were anxious to have fulfilled.

The Newlyn Secretary had only two players left at home, for the rest of his men had either been called up for the RNR or had volunteered for service. However, the Northants and West Yorks Regiments were in training at Penzance at the time and they were immediately keen and eager to play, so a XV was hastily formed and the soldiers went to Porthcurno. Arriving there at a station that had been fortified and was surrounded by sandbags and barbed wire, the soldiers donned the Newlyn jersey and played for the Cornish club. Shortly afterwards they went across to France, where sadly every man taken to Porthcurno lost his life.

During the War, Newlyn RFC lost several fine players including R. Green, RNR, who was drowned in the Dardanelles,; A. Reseigh, one of the first players, drowned in the Mediterranean; W. Pearce, MC, who, killed in France with the South Africans, had been a well-known player on the Rand; R. Harvey, a splendid bustling forward, blown up off Harwich; Walter Nicholls, a young player from Madron, lost his life in Mesopotamia. Several others were badly wounded. W. J. Hosking was wounded in five places, but he came back and played again.

Born and resident in Madron, Walter Nicholls enlisted in Penzance with the 1st/4th Battalion DCLI as a Private, number 2219. He served in Mesopotamia and was killed on the 28th September 1915, aged just 20.

Just as no sector of society was left unscathed, so no sport was left unmarked by the carnage that claimed so many young and vibrant lives from so many nations in a war that ceased with an Armistice a century ago.

To include a list of all those died is an impossibility; instead we must pause for a moment to pay tribute to their sacrifice and to realise how much sport lost through their absence.

Well, battle-hardened men enjoyed different sports, including football, badminton, basketball, boxing, rugby, tug-of-war, swimming etcetera.

Sport – both organised and on a whim – kept them service personnel fit and provided a welcome distraction from the unspeakable terrors of the Great War, which was still never very far away for these brave men.

And when soldiers of all ranks played games or matches together, the strictures of military discipline were temporarily relaxed.

Sports and games were incredibly important to those serving in the forces and many soldiers would use also sports in the trenches to pass the time. The ‘sports’ range from pillow fights, wheelbarrow races and even wrestling on mules. Games played in the trenches were part of the entertainment programme arranged by WWI officers to keep up the morale of the fighting soldiers in the middle of the War.

Aside from the ‘sports’ mentioned above, officers also arranged blindfold squad drill, blindfold driving, tug of war, boat race and high jumps for soldiers in the trenches. These ‘company sports’ were designed to take the minds of WWI servicemen off the battles of the Great War.

Additionally, daily training program in the trenches had the soldiers playing sports and football after their routine exercises which were composed of gas, gun and squad drills as well as pack saddlery.

Starting on Christmas Eve 1914, many German and British troops sang Christmas carols to each other across the lines, and at certain points the Allied soldiers even heard brass bands joining the Germans in their joyous singing.

At the first light of dawn on Christmas Day, some German soldiers emerged from their trenches and approached the Allied lines across ‘No-Man’s-Land’, calling out “Merry Christmas” in their enemies’ native tongues. At first, the Allied soldiers feared it was a trick, but seeing the Germans unarmed they climbed out of their trenches and shook hands with the enemy soldiers. The men exchanged presents of cigarettes and plum puddings and sang carols and songs. There was even a documented case of soldiers from opposing sides playing a good-natured game of football.

Some soldiers used this short-lived ceasefire for a more sombre task: the retrieval of the bodies of fellow combatants who had fallen within the no-man’s land between the lines.

The so-called Christmas Truce of 1914 came only five months after the outbreak of war in Europe and was one of the last examples of the outdated notion of chivalry between enemies in warfare. It was never repeated—future attempts at holiday ceasefires were quashed by officers’ threats of disciplinary action—but it served as heartening proof, however brief, that beneath the brutal clash of weapons, the soldiers’ essential humanity endured.

During WW1 the soldiers on the Western Front did not expect to celebrate on the battlefield, but even a World War could not destroy the Christmas spirit.

Many poems were also written about the First World War, including

‘For the Fallen’, by Robert Laurence Binyon.

It was his best-known poem, composed in September 1914 on the north coast of Cornwall, apparently at Pentire Point, north of Polzeath. An especially well-known verse reads:

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old:

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them.